Just before Easter this year, I heard an interview on Fresh Air with historian Bart Ehrman on his latest book, How Jesus Became God. It was a fascinating interview, which piqued my interest in early Christian history.

As an evangelical, I always felt a bit hazy on early church history. I tried to learn more about it, about what the earliest Christians were like and believed, but finding useful information seemed difficult. I couldn't find very much beyond legend in Christian media, and secular historians seemed hell-bent on destroying any evidence of truth. Aside from the Acts in the Bible, I didn't really know much at all about early Christianity or how the Bible was put together.

I remember sharing this concern with a pastor friend of mine. I wanted to know how the Bible as we know it today became the canon, and why it happened so late after Jesus' life. I knew it was roughly the fourth century, but I was hazy on who and how. To be honest, it really bothered me that a bunch of Roman Catholics (pre-Martin Luther, which meant to my Protestant mind, a very dubious group of church leaders indeed) seemingly sat down and picked and chose which books "fit" and which ones didn't. I could believe that the Holy Spirit directed them to decide which to choose, but I also could conceive of men "misinterpreting" the Holy Spirit and making mistakes. My pastor friend gave me a book he assured me would help me understand how the books of the Bible were chosen.

I read a chapter of the book and put it down. It made no sense to me, was overly academic and really wasn't assuaging my doubts. From then on, I just sort of allowed myself to forget about it. I allowed it to be one of the few intellectual things I'd simply not pursue and let faith in past knowledge and expertise reign. I wasn't one to do that generally; I like to understand how things work and how things came to be and form my own opinions. But this subject was just too deep - and too treacherous - for me to delve any further into.

The NPR interview with Ehrman, a professor of religious studies at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, re-sparked my interest. His newest book, the one he was being interview about, explained how the earliest followers of Jesus likely viewed him as the Messiah in an earthly sense - the literal king of the Jews - but upon believing he had risen from the dead, began to believe he was greater than that. This isn't in and of itself entirely foreign to a Christian believer, but what was fascinating is how the early Christians developed their theology of Jesus. From believing he had been adopted as Son by God upon his death and resurrection, to believing he'd been God incarnate in Mary's womb, to believing he was God before time, the belief in who Jesus was grew and morphed and became increasingly more sophisticated as time - and the educational levels of believers - went on. He uses the New Testament as his primary evidence of these theological changes, using the Gospels and Paul's letters to show the chronological changes in these beliefs through the NT books themselves. I'd read the Gospels countless times, but never realized until he pointed them out, how different each Gospel is - and particularly how different the Gospel of John is, the latest Gospel authored.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. After listening to the interview, I went to order the book. However, it was not yet released at that time, so I ordered one of his older books first, Misquoting Jesus. This book turned out to be the perfect starting point for my studies. It explained how the manuscript we call the Bible today came to be - the very question I'd been wanting answered for years. While it didn't go as late as the Council of Nicaea who eventually formed the canon, it did explain where all the earliest manuscripts came from, and how those manuscripts got copied and distributed. What struck me the most was the fact - one I'd never even heard before - that we don't actually have any of the original manuscripts. Not one. All we have are copies, which were likely copies of copies, if not copies of copies of copies. And of all the copies of each book or letter of the New Testament that are available to scholars today, most of them don't even match each other. Some bear only slight mistakes - spelling, a changed word - but some actually have entirely different sections added or subtracted. Since there is no way of knowing which copies were copied from the originals and which were copied from changed copies, we have no way of knowing what the originals even said.

Furthermore, the originals were not even penned until, at the earliest, twenty years after Jesus' death. The earliest letters of Paul were written twenty years later, and the Gospels were written even later than that, the earliest Gospel Mark being written approximately forty years later and John near the end of the first century, about sixty years later. These were things I'd never known before.

Misquoting Jesus was a good precursor to How Jesus Became God. It laid the foundation of textual criticism which gets touched on in HJBG. Both books were incredibly enlightening. I know I'd never have been able to read them as a Christian; they'd have come across as more secular Christian history bashing. Except for one thing. One thing that would have bothered me deeply.

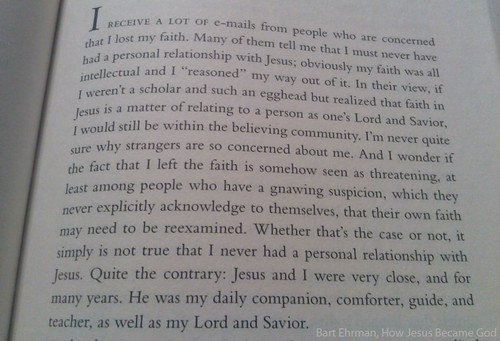

Bart Ehrman was once an evangelical himself. He attended Moody Bible Institute and all.

It was through his study of early church manuscripts and texts that he developed a more "liberal" view of the Bible, seeing it as a very "human" book instead of the inspired word of God. It wasn't this by itself that eventually led to his agnosticism, but it played a large part. Knowing this about his personal history gave these books more credibility to me. He is not a "militant atheist" out to destroy any chance that the Bible might be true. He's a man who once believed in Biblical inerrancy and divine inspiration and who himself once had a "personal relationship with Jesus". He didn't go into the field of textual criticism to debunk Christianity; he went into it to strengthen it.

Bart Ehrman has written several books, and I'd like to get my hands on all of them eventually. The haze of early church beliefs has finally started to lift for me, as I see the Christian religion for what it really was - a fascinating religion that expanded in nuance through time and gained popularity through Roman politics.

No comments:

Post a Comment